Rapid Rise and Fall for Body-Scanning Clinics

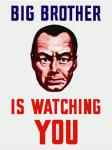

It is uncanny to me that these scanning companies were put out of business so silently. It is like the same mind control that quietly seeps into the subconscious of the masses--like the all pervasive notion that the US public holds that there is 'no such thing as electronic mind control'. The way that Bush got elected and re-elected used this kind of silent sound hypnosis.

This kind of business shut down, I am sure, is being done through silent sound hypnosis technology, broadcasted into the minds of unknowing public over all the networks and clear channel radio stations.

These networks of radio and television are operating monopolies and no one does a damn thing to stop it. It really is eerie how much power the owners of this technology are, they can make monsters out of masses of ignorant victims worldwide.

Susan

Rapid Rise and Fall for Body-Scanning Clinics

By GINA KOLATA

Published: January 23, 2005

or a brief moment, Dr. Thomas Giannulli, a Seattle internist, thought he was getting in at the start of an exciting new area of medicine. He was opening a company to offer CT scans to the public - no doctor's referral necessary. The scans, he said, could find diseases like cancer or heart disease early, long before there were symptoms. And, for the scan centers, there was money to be made.

The demand for the scans - of the chest, of the abdomen, of the whole body - was so great that when Dr. Giannulli opened his center in 2001, he could hardly keep up. "We were very successful; we had waiting lists," he said. He was spending $20,000 a month on advertising and still making money.

Three years later, the center was down to one or two patients a day and Dr. Giannulli was forgoing a paycheck. Finally, late last year, he gave up and closed the center.

Dr. Giannulli's experience, repeated across the country, is one of the most remarkable stories yet of a medical technology bubble that burst, health care researchers say.

It began as a sort of medical gold rush, with hundreds of scanning centers, with ceaseless direct-to-consumer advertising, and with thousands of Americans paying out of pocket for the scans, which could cost $1,000 or more.

It ended abruptly with the wholesale shuttering of businesses.

CT Screening International, which scanned 25,000 people at 13 centers across the nation, went out of business. AmeriScan, another national chain, also closed. So, radiologists say, did another company that put scanners in vans and traveled to small towns in the South.

The business's collapse, health care researchers say, holds lessons about the workings of American medicine.

It shows the limits of direct-to-consumer advertising and the power of dissuasion by professional societies, which warned against getting one of these scans. The tests, they said, would mostly find innocuous lumps in places like the thyroid or lungs, requiring rounds of additional tests to rule out real problems, and would miss common cancers, like those of the breast.

It also shows the workings of the medical market - when insurers refused to pay, requiring customers to dig into their own pockets for the tests, scanning centers found themselves cutting prices to compete. Within a year, some centers said, prices fell to less than $500 from $1,000 or more.

And when the flow of patients began to slow, the combination of low prices and reduced business spelled doom. It turned out that the assumption by radiologists - that people would be willing to pay for early detection by scans and that there was a huge market waiting to be tapped - were not true.

The scans were something new in American medicine - not like traditional screening scans, mammograms or colonoscopies, for example, in which patients are overseen by their doctors. People requested these scans on their own. They paid on their own, with no hints that insurers would start picking up the bill. And the reports came to the customers, not their doctors.

Some proponents said the scans would enable people to take their health care into their own hands. Critics said the scans were medical nightmares, a powerful medical technology gone out of control.

But few anticipated the precipitous reversal of fortune for the scanning centers.

In Seattle, Dr. Scott Ramsey of the University of Washington got a federal grant to study patients at nine centers, expecting to enroll 1,500 patients. Last year, when he was ready to begin, only two centers were left, and he enrolled just 50 patients.

He also hoped to do a study with a company, ScanQuest, on the scans' effectiveness. "We were in negotiations when they suddenly stopped returning our phone calls," Dr. Ramsey said. It turned out that ScanQuest had gone out of business.

"I've never seen a market for a medical technology collapse so completely," Dr. Ramsey said.

Whole body scans erupted onto the national scene in 2000, helped in large part by Dr. Harvey Eisenberg, the owner of HealthView, a scanning center in Newport Beach, Calif. Oprah Winfrey, scanned there, featured him on her show, and his competitors watched with interest as he got attention on morning shows like "Good Morning America" and "Today" as well as in newspapers and magazines like USA Today and Men's Health. Soon, HealthView's waiting list grew to eight months.

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/23/health/23scans.html

This kind of business shut down, I am sure, is being done through silent sound hypnosis technology, broadcasted into the minds of unknowing public over all the networks and clear channel radio stations.

These networks of radio and television are operating monopolies and no one does a damn thing to stop it. It really is eerie how much power the owners of this technology are, they can make monsters out of masses of ignorant victims worldwide.

Susan

Rapid Rise and Fall for Body-Scanning Clinics

By GINA KOLATA

Published: January 23, 2005

or a brief moment, Dr. Thomas Giannulli, a Seattle internist, thought he was getting in at the start of an exciting new area of medicine. He was opening a company to offer CT scans to the public - no doctor's referral necessary. The scans, he said, could find diseases like cancer or heart disease early, long before there were symptoms. And, for the scan centers, there was money to be made.

The demand for the scans - of the chest, of the abdomen, of the whole body - was so great that when Dr. Giannulli opened his center in 2001, he could hardly keep up. "We were very successful; we had waiting lists," he said. He was spending $20,000 a month on advertising and still making money.

Three years later, the center was down to one or two patients a day and Dr. Giannulli was forgoing a paycheck. Finally, late last year, he gave up and closed the center.

Dr. Giannulli's experience, repeated across the country, is one of the most remarkable stories yet of a medical technology bubble that burst, health care researchers say.

It began as a sort of medical gold rush, with hundreds of scanning centers, with ceaseless direct-to-consumer advertising, and with thousands of Americans paying out of pocket for the scans, which could cost $1,000 or more.

It ended abruptly with the wholesale shuttering of businesses.

CT Screening International, which scanned 25,000 people at 13 centers across the nation, went out of business. AmeriScan, another national chain, also closed. So, radiologists say, did another company that put scanners in vans and traveled to small towns in the South.

The business's collapse, health care researchers say, holds lessons about the workings of American medicine.

It shows the limits of direct-to-consumer advertising and the power of dissuasion by professional societies, which warned against getting one of these scans. The tests, they said, would mostly find innocuous lumps in places like the thyroid or lungs, requiring rounds of additional tests to rule out real problems, and would miss common cancers, like those of the breast.

It also shows the workings of the medical market - when insurers refused to pay, requiring customers to dig into their own pockets for the tests, scanning centers found themselves cutting prices to compete. Within a year, some centers said, prices fell to less than $500 from $1,000 or more.

And when the flow of patients began to slow, the combination of low prices and reduced business spelled doom. It turned out that the assumption by radiologists - that people would be willing to pay for early detection by scans and that there was a huge market waiting to be tapped - were not true.

The scans were something new in American medicine - not like traditional screening scans, mammograms or colonoscopies, for example, in which patients are overseen by their doctors. People requested these scans on their own. They paid on their own, with no hints that insurers would start picking up the bill. And the reports came to the customers, not their doctors.

Some proponents said the scans would enable people to take their health care into their own hands. Critics said the scans were medical nightmares, a powerful medical technology gone out of control.

But few anticipated the precipitous reversal of fortune for the scanning centers.

In Seattle, Dr. Scott Ramsey of the University of Washington got a federal grant to study patients at nine centers, expecting to enroll 1,500 patients. Last year, when he was ready to begin, only two centers were left, and he enrolled just 50 patients.

He also hoped to do a study with a company, ScanQuest, on the scans' effectiveness. "We were in negotiations when they suddenly stopped returning our phone calls," Dr. Ramsey said. It turned out that ScanQuest had gone out of business.

"I've never seen a market for a medical technology collapse so completely," Dr. Ramsey said.

Whole body scans erupted onto the national scene in 2000, helped in large part by Dr. Harvey Eisenberg, the owner of HealthView, a scanning center in Newport Beach, Calif. Oprah Winfrey, scanned there, featured him on her show, and his competitors watched with interest as he got attention on morning shows like "Good Morning America" and "Today" as well as in newspapers and magazines like USA Today and Men's Health. Soon, HealthView's waiting list grew to eight months.

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/23/health/23scans.html

Omega - 23. Jan, 19:02